“Economists believe in full employment. Americans think that work builds character. But what if jobs aren’t working anymore?” — James Livingston in Fuck Work

Many industries—music, publishing, media—have become disintermediated by the internet. Platforms like YouTube, Medium, and Twitter have flourished by democratizing access to a wider group of participants. Gatekeepers removed, permission no longer required.

Yet, curiously, while it’s become increasingly common to expect open and free access in many aspects of our lives, work has not undergone such a transformation. The power still overwhelmingly resides in the hands of employers. They are the gatekeepers for our conventional model of economic participation: the job.

The line between employers and employees is distinct. Us, the owners. Them, the workers. Or vice-versa. The two groups have different incentives and motives, and there is a clear delineation between the two. This separation is common in all but one industry: tech.

Whether as a result of a competitive labor market (most likely) or a good-willed-nature of tech companies (less likely, but plausible), it has become both common and expected that as an employee you will receive stock options.

As an instrument, employee stock option plans (ESOPs) blur the lines between employer and employee. They incentivize an employee to act like an owner because, well, they are! They help to keep everyone pulling in the same direction by ensuring that what is good for the company, is good for the employee.

(Invented by lawyer-economist Louis O. Kelso as a “revolutionary plan for a capitalistic distribution of wealth—to preserve our free society”, the ESOP has an interesting history if you’re curious.)

The benefits of stock ownership are easy to understand and are supported by success stories like that of artist David Choe. In 2005, he painted a mural at the Facebook office in exchange for stock. When Facebook went public his stock ended up being worth $200M!

Alas, in practice, ESOPs are not always favourable for the employee. In fact, being granted options has often traditionally been a kind of “gotcha!”.

The trouble is that the legal terms of ESOPs, like most company agreements, favor and protect the employer, not the employee. This leads to an incentive scheme that turns into a pair of golden handcuffs. Stay and you may be rewarded. Quit or have something happen that causes you to leave and you will likely end up with nothing.

There are many issues with today’s common option plans. Sam Altman has spelled out some of them in his Employee Equity post.

I believe that two of the most problematic aspects of employee equity has to do with exercise rights and transfer rights.

Exercise Rights

You’re not an actual shareholder until you exercise your options. Commonly however, employers restrict employees from exercising until a trigger event: the company is acquired, goes public, or the employee leaves the company.

The first two situations are great. That’s what you want to live through. However, the most common situation is the latter: you’ll have an opportunity to exercise your options because you’re leaving the company.

And here’s the first gotcha: when an employee leaves it is very unlikely that they will actually be able to acquire their options.

Suppose you were granted 100,000 options at a strike price of $1.00. At the time of exercise, the company has grown and so has the value of each share. Let’s say it’s now at $10/share.

Since your strike price was $1.00/share, your exercise price is $100k. However, because the shares have increased in value between then and now, the total value of your options is now $1M. That is a big payday!

Or is it?

To acquire your shares, you’ll have to do two things:

- Pay the exercise price ($100k)

- Pay capital gains taxes on the difference ($900k) at about a 20% rate ($180k)

Therefore, to fully exercise your options, you’re going to have to come up with $280k. And you only have 90-days to do that. And if you don’t? You forfeit your options and they are returned to the company.

😐

Unless you stay at the company until it goes public (or gets acquired) you really have no other choice but to forfeit your options.

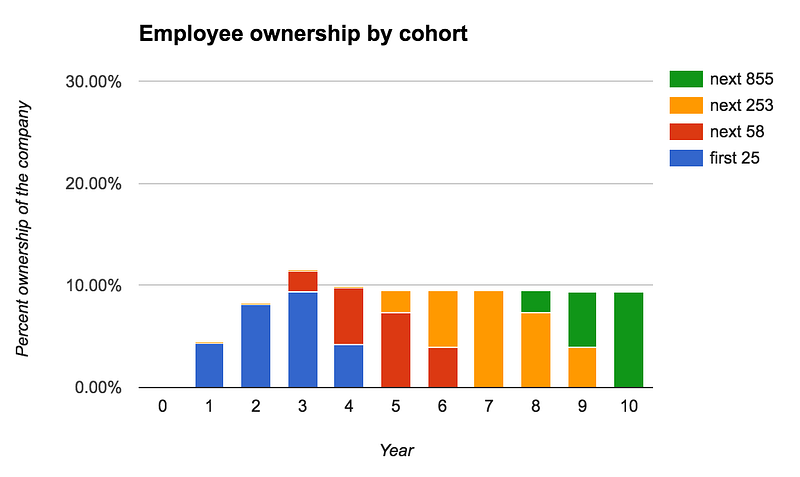

This graph, which shows hypothetical employee ownership across employee cohorts throughout the lifecycle of a typical private company, illustrates the problem.

The exercise rights on most employee option plans is exploitative because, in reality, most employees don’t get to exercise their options. It’s just too expensive to do so, and the window of time is too short.

The balance of power favors the employer. ESOPs seem like an equitable thing to do, but in practice they amount to very little.

—

TL;DR: exercise windows are too short and options are too expensive so employees end up forfeiting their options. Key ideas:

- Implement a 10-year exercise window

- Facilitate a cashless exercise process by withholding an amount of shares equal to the exercise price

Transfer Rights

Options aren’t just a bonus on top of a handsome salary. In most cases, people are taking a pay cut in exchange for their option plan. Options are part of a total compensation plan, not a nice-to-have thrown on top.

The above (hypothetical) graph may suggest that you’d be better off taking a higher wage and forgoing the options altogether. But let’s stay optimistic for a moment and take a gamble on getting a David Choe-type payout if the company does go public.

Well, you’ll likely then run into another feature (bug?) of options: they are an illiquid asset.

Sure, secondary markets exist for buying and selling private stocks, but most stock option plans prohibit this. Even if you could exercise your options, the company wouldn’t let you sell your shares to a buyer even if you found one.

The terms of the options agreement typically forbid an employee from doing two things:

- Exercising their options before a trigger event (acquisition, IPO, leave)

- Transferring their shares if they were able to exercise them

This is a problem considering that the average age of a company before it IPOs is now 11-years compared to 4-years during the dot-com era. (The remnants of this can be seen in the standard 4-year vesting schedule.)

Life happens. Maybe your family has grown and you need to move into a larger home. Maybe you’ve had something tragic happen —a health crisis, or death in the family— and you need extra cash.

So here’s the second gotcha. If you’re an employee taking a reduced salary in exchange for options as part of a complete compensation package, you’re left with less cash and an illiquid asset that is restricted from being transferred in any form—unless you wait the ~11 years to see if the company is one of the lucky few to IPO (or get acquired).

The fact that a company restricts transfers once again renders options far less meaningful than they appear.

A company doesn’t have to go full burning man to allow transfers. You don’t have to put your copy of Atlas Shrugged in the freezer. You can do this and still be a smart, cunning, profit seeking capitalist—while also making work better for employees. Be an active participant in this process. Facilitate fairtransfers to other employees or vetted outside buyers.

—

TL;DR: options are illiquid and come with harsh transfer restrictions. Key ideas:

- Allow employees to exercise their vested options whenever they want

- Facilitate buy-backs and transfer programs for fully vested shareholders

On Making a Better Option Plan

At Colony, we’ve worked (for a much longer time than we anticipated) to make a better option plan. Today we would like to open source it.

It’s not perfect. We haven’t found one that is. But we think it’s an improvement in four notable ways:

- We’ve implemented a 10-year exercise window

- We’ve allowed for a cashless exercise

- Employees may exercise their vested options whenever they want

- We facilitate a buy-back and transfer program for fully vested shareholders

The fourth point is something we’re really enthusiastic about. Instead of fearing transfers and imposing a ban, we will play an active role in facilitating a healthy process for employees to liquidate a portion of their options. Subject to change, our plan goes something like this:

Starting after the initial grants have fully vested, we’ll run an annual buy-back program that allows vested option holders who’ve exercised some or all of their options to sell a portion of them to approved participants.

Buyers will be prioritized in this order:

- The company

- Other employees

- Outside buyers

For sales to outside buyers (on secondary markets or elsewhere), we’ll play an active role in facilitating a mutually favourable experience instead of just throwing a blanket “no” across all sales. Sales have a few ground rules to help things go smoothly:

- A buyer must first be found and nominated by a participating seller

- The company must approve, and won’t unreasonably deny the buyer

This process, we think, will allow the employees to realize liquidity of their vested exercised shares while allowing the company to have a healthy degree of control over the process.

This is still very experimental for us, and the first event has not yet happened, but we have created our legal documents in a way such that we can—and will.

But Why?

Why are we doing this? Why did we turn one month of legal work into more than six? It’s a pretty simple philosophy: make work better by redistributing the balance of power between owners and workers.

This is central to the work we’re doing at Colony. We are building a protocol and platform that enables anyone to earn a stake in a project based on the value they contribute. Remove unnecessary hierarchy; allocate wealth proportionally to one’s contribution.

Sure, this is just a start, but laying down solid legal foundations is an important step towards a better future of work for all.

Thanks to Jack du Rose and Griffin Ichiba Hotchkiss for reading early drafts and giving valuable feedback, and to our legal team for putting up with our incessant request when crafting this plan.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Colony makes it easy for people all over the world to build organisations together, online.

Join the conversation on Discord, follow us on Twitter, sign up for (occasional and awesome) email updates, or if you’re feeling old-skool, drop us an email.