Empowering Decentralized Meritocracy: The Heart of Governance

The Colony protocol aims to enable the creation of decentralized organizations that are broadly meritocratic, meaning that when it comes to decision-making and power, it’s merit (rather than say, wealth or status) that should determine who has influence.

Merit is a tricky concept to measure, let alone to decentralize. People are complicated.

Given high marks in a maths exam, it’s still difficult to tell if someone would make a good professor or not. Given a high credit rating, it’s downright impossible to tell if someone would be good at tuning pianos.

Let’s take a less arbitrary example: Imagine you’re a CEO trying to fill an important position. How would you decide on the right person for the job?

You could take a handful of the rating systems or exams relevant to the job (SAT, IELTS, GMAT, GPA, LSAT, CCNA, and other various imposing acronyms). You’d likely look at some historical documentations of work done (writing samples, github commits, etc.). Unintentionally, you might fall back on more informal and problematic proxies for merit (endorsements, university diplomas, age, nationality, gender, charisma, physical appearance).

Most of the time, it’ll end up being a mix of all these combined with some fuzzy intuition about which are the most important.

All of the factors above are approximations of merit, which we might generally call reputation, because they are all to some extent second-hand information, and although each is designed to capture merit in some way, we wouldn’t want to say that any one of these metrics actually is merit.

Reputation is everything.

In Colony, it is reputation, rather than voting, that keeps things moving.

Voting has a place within community governance, but bureaucracy is stifling in the day to day activities of a company, and shouldn’t be necessary for a decentralized organization to function. In fact, voting on everything is a sure-fire way to ensure that nothing gets done.

“I have called this shareholder meeting to vote on reimbursing Lee from accounting for a taxi fare from last Wednesday.”

— No CEO, ever.

Instead, reputation is the driving metric that allows people to make executive actions using shared resources, such as using funds from a pot to have the colony piano tuned. The greater one’s reputation, the more executive authority one has within the colony to make things happen. No voting necessary.

Reputation scores encapsulate everything about what work you did, how much that work was worth, what your peers thought of your work, how long you’ve been doing work, etc. — and the system uses that score to dynamically mediate organizational activity, including a member’s ability to fund tasks and resolve disputes.

Reputation can be gained by completing tasks within the colony, evaluating the quality of other’s tasks, or administrative work like flagging bad behavior.

Reputation is organized by domains and tagged with different skills, so that colony members gain influence only in the areas of their expertise. This means the piano tuners, no matter how talented they are, won’t be able to dip in to the dev team’s working capital.

Finally, reputation decays over time. Persistent and regular contribution toward a colony is the only way to stay influential.

The thing about reputation is that it has to be this complex in order to be useful. The more nuanced a system of reputation is, the better it aligns our expectations of performance with reality — which means that true merit is being better represented, and a true meritocracy can form on the blockchain.

But does it scale?

Complexity comes at a cost. In Ethereum, that cost is explicitly defined in terms of gas. The more complex the calculations written into a smart contract are, the more costly they become to the user. More significantly, the gas limit imposes an upper bound on the complexity of any operation performed within a block.

The unfortunate reality is that the computational work required for the colony reputation system described by the whitepaper far exceeds Ethereum’s gas limit.

However, while the calculations required for reputation might be too taxing to do inside the Ethereum Virtual Machine, out in the off-chain world the work is really quite easy. A Raspberry Pi could do them.

Nevertheless, the decentralized governance of a colony requires the smart contracts being able to reference reputation scores. Reputation has to be put on the blockchain somehow, right?

Actually, no! Not really.

The reason it doesn’t need to be on chain is that reputation is entirely deterministic and calculated from on-chain events.

Using the transaction and account records residing on the blockchain, anyone could perform a calculation that tabulates the global state of all reputation for all colonies. The results of that calculation, if done correctly, would be the same for everyone.

So, rather than calculating reputation scores on-chain, users submit a transaction to the contract which contains their score, together with a proof that the score is consistent with the global state of reputation.

Combine user-submitted scores with a little game theory to properly align incentives (more on that later), and we have a system that scales quite nicely.

No matter how many colonies, domains, skills, or tasks, the reputation system will only ever need 32 bytes on-chain. Huzzah!

Merkling in the Colony Protocol

The handy mathematical concept that makes this possible is an indispensable tool for blockchains: The Merkle tree.

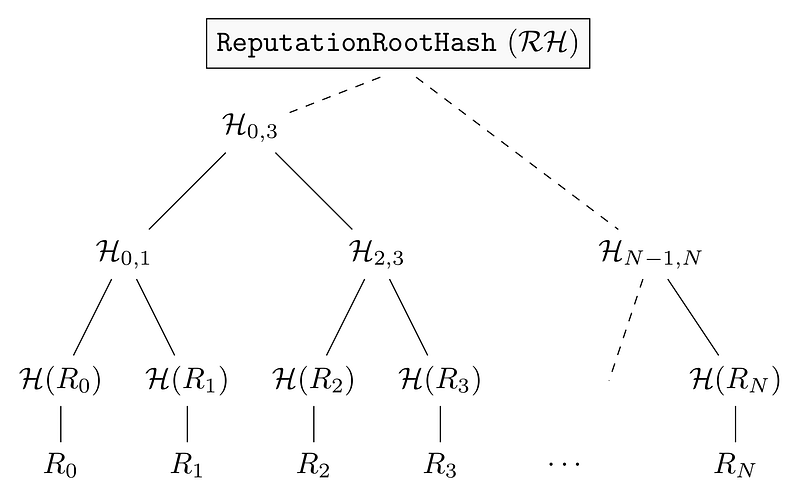

Merkle trees allow us to take an arbitrarily large data set (such as the set of all reputation scores for all colonies, domains, and skills) and distill that information down to a single small number (of length 32 bytes). That special number, called the Merkle root, represents a sort of fingerprint for the larger set, which can be used to verify claims about the set’s members.

Here’s how it works in the Colony Reputation system:

A reputation score is hashed, then paired with an another hashed reputation score. The pair is hashed again to create a single digest that represents 2 scores. Two of those second-order hashes are then hashed again to create a digest that now represents 4 scores. The hashing continues pairwise until we’re left with one single digest, called the ReputationRootHash, which represents the global state of all reputation scores.

A user submitting a transaction to a colony contract will include in the transaction two values:

- The reputation they claim to have.

- A Merkle proof that their reputation is an element in the set of all reputations on the network.

The colony contract can verify on-chain that these two values are consistent with the ReputationRootHash, and may then use the provided reputation score without actually needing to calculate or even access the global state of reputation on the Colony network.

All of the hard work stays off the chain, but the smart contracts can still make use of reputation scores. Everyone wins!

[A note from Alex Rea: The above description is representative of the whitepaper currently, but we have since realized that a Patricia tree is able to be used for this with a much smaller overhead for the reputation miners. It stores exactly the same data, just more efficiently, and is still uniquely represented by a ReputationRootHash .]

Reputation Mining, CLNY, and the Burden of Proof

The last piece of the reputation puzzle is getting all members of the Colony network to agree on a single ReputationRootHash. This is accomplished by a process we call Reputation Mining.

Since the root hash can’t be calculated on-chain, it has to come from an off-chain source who is faithfully recording and calculating the global state of reputation. Once calculated, it is submitted to the blockchain in a transaction. This process happens continuously over a defined period, so that global reputation scores are always fresh.

The reputation mining process works on an “innocent until proven guilty” principle: Although it’s impossible for a valid hash to be proven true on-chain, it’s relatively straightforward for an invalid hash to be proven false.

In the event that two submitted hashes differ, the false one can be fleshed out through an automated justification process that will eventually zero in on the exact on-chain events that differ between the two submitted hashes.

Because these events can be verified by a smart contract, the bad actor will be automatically punished for a false submission, and will lose their CLNY deposit.

This process only ever requires one honest submission every update period, instead of 51% of all submissions, as is the case with proof-of-work mining.

Conclusion

In the end, Colony’s vision of a decentralized meritocracy works precisely because we have something in the blockchain that the ‘real world’ does not: a complete record of all tasks. The reputation system isn’t actually modifying that consensus or recording something new — it’s just compressing information we already had into a more legible and useful form for both smart contracts and humans.

The process of reputation mining is a platform-specific solution to a much broader set of scaling challenges facing Ethereum — our approach might be limited in scope and application, but it’s one attempt among many to overcome the limitations of today’s blockchain, and work towards a better, more efficient, decentralized future.

Griffin is a writer with a particular interest in the blockchain’s promise for the developing world.

He has lived in Yangon, Myanmar for the last 5 years, but now wanders around, usually in a westerly direction.

He enjoys harrowing motorcycle journeys with a side of photography.

Colony makes it easy for people all over the world to build organisations together, online.

Join the conversation on Discord, follow us on Twitter, sign up for (occasional and awesome) email updates, or if you’re feeling old-skool, drop us an email.